Not Even God Could Win this Game

What chess and the Dunning-Kruger effect teach us about the Gospel

Have you ever spoken with someone so excited about what they were explaining that they went bug eyed? This was the expression on the face of a priest in our community as he told me about how good at chess the AI program Stockfish is. Unlike this priest, I didn’t go to MIT when I was sixteen, or work for Steve Jobs at NeXT Inc., so I’m probably only partially aware of just how much of the conversation went over my head. While I couldn’t fully relate with the finer technical nuances, I could see and relate with this priest’s amazed passion. After walking me through a particularly impressive feat of calculation this program routinely achieves, he exclaimed “This is how God plays chess!”

One thing which helped me grasp the challenge of making a program which could even competently play chess was learning about the absolutely staggering number of possible moves in any given game. As many have pointed out, there are more possible moves in chess than there are atoms in the observable universe. This video does a fantastic job explaining how this number was arrived at:

How do you even begin to manage that type of immense, unfathomable complexity? Certainly not through brute force (i.e. testing all of the possible combinations of moves). This puzzle has placed chess at the forefront of the machine learning movement. For decades mathematicians and computer scientists have striven to create more and more efficient means for computers to learn chess. The first time a chess program beat a human world champion in an official match was in 1996, when an IBM supercomputer named Deep Blue defeated Gary Kasparov. Against Deep Blue, Kasparov had a fighting chance; he even managed to win two of the six games. Had the iconic match been held under different conditions (e.g. greater transparency about Deep Blue’s playing tendencies) and had Kasparov played closer to his normal standard, he might have won. But since then, computers have left humans so far in the dust that we don’t even bother having matches like this anymore.1 It would be like watching a human trying to arm wrestle a gorilla.

Another thing that helped me appreciate how good Stockfish is was coming to a better understanding of just how good the top human player is. I had already known Magnus Carlsen was a multi (now five) time world champion and the number one ranked player (now for over ten years). But what most vividly made me aware of the skill gap between myself and him was a scene from the documentary Magnus. In the film, Carlsen visits Harvard University and plays ten lawyers. Granted, none of these lawyers were professional caliber players. But they were still serious Ivy League-educated hobbyists, Carlsen was playing all ten games at once, and he was blindfolded. Not only did Carlsen beat all ten Harvard lawyers while blindfolded without breaking a sweat, to top it all off he also wrote down every move from their games from memory after signing autographs.

Thinking about what it would take for me to do something like this brings to mind a line from one of Bill Burr’s comedy specials. While marveling at the life of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Burr asked:

Anybody here think they could move to Austria, learn the language, become famous for working out, then be a movie star, then marry into their royalty, and hold public office? How many lifetimes would you need?? I’m on my third attempt at Rosetta Stone Spanish!

Someone who didn’t seem to share this perception was Max Deutsch, a chess novice who challenged himself to learn chess well enough to beat Carlsen in just thirty days. At the time Deutsch was documenting a year long experiment where he’d attempt to learn one new skill each month. I actually think this was a fascinating and inspiring project overall, and some of things he achieved were genuinely impressive. However it’s one thing to learn how to solve a Rubik’s cube, or draw a self portrait, or do a back flip in a month. It’s another to seriously entertain the thought of beating a world champion after only a months study. As one commenter put it, ‘I learned how to do a backflip in a month. For my next trick, I will win a gold medal in gymnastics!’

This strange episode was chronicled in this article and in this video:

I have to give The Wall Street Journal credit here, the way they were able to paint a publicity stunt for Carlsen’s PlayMagnus app into a suspenseful and thought provoking underdog tale shows masterful storytelling ability. But we could have safely categorized this as impossible even if the challenge was to beat the best player at a local coffee house chess club.

To be fair to Deutsch, he admits he quickly realized he couldn’t learn chess quickly enough through normal means, which is why he attempted to create and memorize an algorithm crudely mimicking machine learning programs like Stockfish. The algorithm in my opinion only made his challenge slightly less ludicrous. Just a functional algorithm would require him to memorize tens of thousands of chess positions. You can read Deutsch’s side of the story on his personal Medium page. Some of his daily updates during the challenge are downright fascinating. Sometimes (in fact, most of the time) he seems fully aware of how impossible his goal is, writing things like this:

But, this offered an interesting opportunity: Unlike my other challenges, where success was ambitiously in reach, could I take on a completely impossible challenge, and see if I could come up with a radical approach, rendering the challenge a little less impossible?

But I’m not letting him completely off the hook because of passages like these:

These friends do have a point: This month’s challenge (defeating Magnus Carlsen at a game of chess) is dancing on the boundary between what’s possible and what’s not.

and

Thus, my hope with this project was to pick ambitious goals that rubbed right up against this failure point, pushing me to grow and discover the outer limits of my abilities.

This challenge didn’t rub right up against Deutsch’s failure point, it broke the sound barrier as it crossed over it. Even taking him at his word that he knew the challenge was impossible (I do), it seems he still astronomically overestimated what was possible. Nonsense lines from the WSJ article like “after eight moves, using his own limited chess ability, the unthinkable was occurring: Max was winning” showed that that the journalists didn’t fully grasp this either.2

I don’t fully blame Deutsch. Psychology has shown that we’re bad at judging the skill gap between professionals and amateurs. As humans, we can’t help but believe that no matter how lopsided a competition may appear, every fighter has a ‘puncher’s chance.’ There’s a reason Rocky is one of the most famous and beloved movies of all time. It speaks to the hope we have that if we work hard and catch a few breaks, there’s nothing we can’t achieve. And sometimes suspending our judgment that something is impossible allows us to approach a problem with the freedom and creativity to solve it, or at least to discover new and exciting paths forward. But I think this is best done only after you have learned and come to terms with the true nature of the challenge, and gained genuine self knowledge about your relative ability.

You may be aware of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, which states that the less we know about a subject or activity, the more likely we are to overestimate our knowledge and competence in that skill. It’s especially easy to underestimate the skill of people who aren’t quite at the top of their domain. Contrary to the mocking cries of those who wonder why I root for the Detroit Lions, there are no bad football players on that team. Each and every man on the roster is a freak of nature who would be the best player by a mile on any high school team and all but a handful of college teams. The idea that they are bad at football is an illusion created by the fact that they are playing against other NFL players. The fact that they don’t hold up against the top .0001% of players still leaves them in the top .001 percentile.

In a similar vein Youtuber JxmyHighroller has an entertaining video about retired NBA player Brian Scalibrine’s quest to vindicate himself against amateurs who thought they could beat him in a one on one game. Everyone understands they couldn’t beat Lebron James, and on some level we realize that all NBA players are literally out of our league. But when we see how hapless NBA players like Scalibrine are against Lebron, part of us can’t help but think we’d stand a chance against the former. Again, an understandable illusion, but nevertheless totally delusional. Seeing a long retired, now ordinary looking former NBA benchwarmer in his 40s completely demolish a guy who had started in the ACC a year prior was a real eye opener for me. Even if you’re good enough to have your play televised on ESPN, you can still be a speck. To all those who scoffed at his low playing time and mediocre stats (and to one heckler in particular), Scalibrine sent a clear message “I’m closer to Lebron than you are to me.”

Why am I beating this point to death? Recall that knowing how good Carlsen is helped me appreciate how good Stockfish is. To sum up what I’ve been saying, we can confidently say that in the game’s 500 year history, and out of the billions of people who have played it, no one was ever better at chess than Magnus Carlsen. He arguably has no close rival. And yet if he played Stockfish he would not win a single game. Aside from a stronger chess engine, only God could beat Stockfish. And God, who is aware of all 10^120 possible moves in Chess, obviously wouldn’t struggle against Stockfish, although now you hopefully have a better idea of just how good at chess God is.

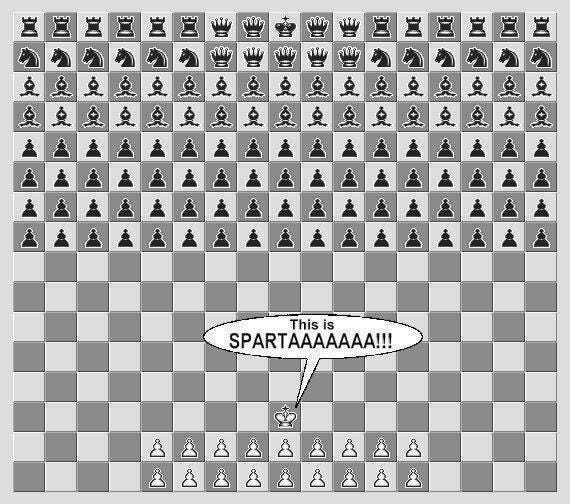

At this point some of you may be asking: “John, did you write all of this just to tell me that God is good at chess?” Hold your horses! Yes, it’s no surprise that God could beat Stockfish. But what you might find surprising is that there are some instances where God can’t win. Several years ago, when I was still on Facebook, I came across this image:

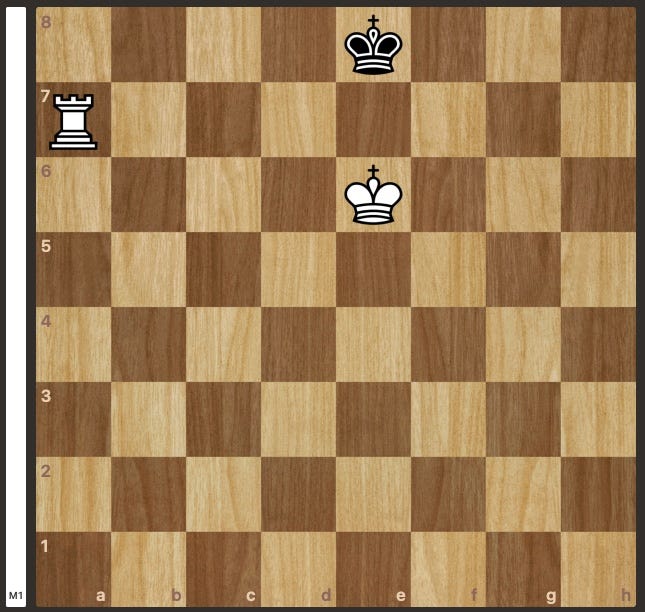

Even in this scenario, there were people who didn’t seem entirely sure white’s position was hopeless. But one annoyed commenter shut down this talk and didn’t mince words: ‘Not even God could win this game.’ That’s only a slight exaggeration. Black could let God win by intentionally making bad and pointless moves. But against any opponent who knows the rules of chess and is trying to win, God doesn’t stand a chance. He could change the rules of chess. He could threaten and chastise his opponent until they resigned. God’s best bet would be to trick his opponent into triggering a draw by stalemate. But he couldn’t win. And in this next position (a classic checkmate pattern) God couldn’t win even if his opponent tried to let him win.

Many are uncomfortable with speaking about God in this way. In fact, one of the greatest divisions between Catholics and the Reformed tradition is over the issue of predestination. Catholics believe we cooperate with God in our salvation through our free acceptance or rejection of God’s gift. Reformed Christians vehemently protest that this puts limits on God’s sovereign authority to save whoever he wants. Although I’m not a theologian and don’t have space to do this topic justice, I think the above chess positions nicely illustrate the Catholic view.3 God can’t win those games, not because he’s bad at chess, but precisely because he’s chosen to play chess, and therefore to limit his actions to the parameters set by the game. When it comes to our salvation, if I reject God, he cannot save me, not because he isn’t all powerful, but because he’s chosen to play the only game worth playing, and therefore to limit himself to its parameters. That game is the game of love, and love can only exist where there is genuine freedom.

Whatever role we think our cooperation plays in our salvation, all Christians believe that we need to cooperate. We need to cooperate because original sin created an unbridgeable (humanly speaking) gap between God and Man, and because we must do battle with the effects of sin every day in our own lives and in the world around us. The heretic Pelagius believed that we have a punchers chance against the devil; that it wasn’t just possible in principle for us to win, but that victory was assured if we just followed the rules and lived a good life. St. Augustine knew better. Through his superior grasp of the scriptures and through his own struggles with sexual sin, he recognized (most eloquently in his classic work Confessions) that overcoming sin is beyond our natural ability. We need God’s grace.

Thus, anyone with a works based mentality to salvation has no right to scoff at Deutsch for being overconfident. Imagining Max Deutsch playing Magnus Carlsen gets you thinking in the right direction in terms of our odds. Imagining Deutsch playing Stockfish gets you closer. But the two chess positions above gets you the closest. We couldn’t win even if the devil tried to lose.4

To win, we don’t need a new strategy, we don’t need more practice, and we don’t need a more advanced computer program; we need a new game. To overcome sin, we don’t need more willpower, more good deeds, or a better character. We need a new life. Jesus became a chess player. By dying he allowed us to join his game, by rising he allows us to share in his victory. In order to play his game, (and thus to have any hope of winning) we need to play his moves. This is why the saints were so focused on only doing God’s will. It’s why the late founder of the Companions of the Cross, Fr. Bob Bedard would always say “the only thing worth doing is God’s will.” God knows all the possible outcomes, he sees what you couldn’t even with a hundred lifetimes. His will is not just the only thing worth doing, it’s the only thing that makes any sense.

For a more recent man vs machine story, check out this documentary about the AI program AlphaGo, which became the first program to beat a world champion at the game Go in 2016.

Here is my favorite chess YouTuber breaking down Carlsen and Deutsch’s game

For anyone interested in taking a deeper dive into Catholic and Reformed disagreements on the role of human freedom in light of predestination, I have two suggestions:

This debate, aside from being highly educational, is also one of the most entertaining and competitive debates I’ve seen on any subject:

One of my professors, Dr. Eduardo Echeverria, world renowned for his ecumenical scholarship, gives an in depth examination of how to reconcile human freedom with grace and predestination in his book Divine Election: A Catholic Orientation in Dogmatic and Ecumenical Perspective. You can buy it here.

See Catechism of the Catholic Church 385-425 http://www.scborromeo.org/ccc/p1s2c1p7.htm

Think the ten player stunt is just that...all he does is play the previous players move next on the following players board, and does it quickly so generally maintaining an advantage both psychological and tactical. Usually works thru probability...memory of last 2 moves all that is critical???