Welcome to the tenth entry of The Monday Mystery. Each week I will write a reflection on a mystery (i.e. an episode in the life of Jesus or Mary) from the Rosary. My hope for this series is to provide fuel and inspiration for your own meditations. When you finish reading the reflection, I encourage you to do a ‘test run’ of the mystery by praying a decade of the Rosary (i.e. one Our Father, ten Hail Marys, and one Glory Be) while meditating on the mystery.

If someone could only read one self-help or personal development book, I’d tell them to read The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey. I’m aware that for many, this book and its catchphrases have become unsalvagably clichéd. If that’s you, I encourage you to take a second look, and try your best to see past the accumulated disappointment and annoyance you may associate with it. Don’t let the superficial and glib ways Covey’s message may have been presented to you keep you from taking advantage of its wisdom.

I recommend The 7 Habits so highly not just because it’s my favorite book in the genre, but primarily because I think it does the best job of presenting the full picture of personal improvement. I think Covey achieved this because he took the time to intensively survey the self-help and wisdom literature down through the centuries. Many books are limited by the fact that at the end of the day, they’re just a collection of one random person’s random nuggets of wisdom. To be fair, the 7 Habits are also a collection of nuggets, but they’re a synthesis of thousands of nuggets from hundreds of wise teachers. If you read other books, you might very well find better and more helpful articulations of Covey’s nuggets. But I don’t think you’ll find an overall arrangement that’s more complete, coherent, and practically useful.

One of the most impactful of the seven habits is habit number two: begin with the end in mind. Effective people are empowered by their focus and clarity of vision: they know what they want, and they make decisions by working backwards from their end goal to find out what it will take to achieve it. In this post I’d like to apply this to an activity Christians do every week: going to church.

What is church? Our english word ‘church’ comes from the greek word ‘ekklesia,’ which means ‘assembly.’ From the very beginning of Christianity, Jesus’ followers would assemble (i.e. go to church) on Sundays to carry out his instruction at the Last Supper to “do this in memory of me” (Luke 22:19). In our day, I think ‘do’ is a key word. Unfortunately it’s all too common for people to attend church with a passive, consumerist, and individualist mentality. There’s little to no sense that we’re there to ‘do’ anything. As a missionary, I spoke with many people who stopped going to church because they weren’t ‘getting anything out of it.’ While it’s true that we can and should ‘get something’ out of church, that’s not the point.

So what is the point? What exactly are we ‘doing’ in Jesus’ memory? And why did this practice in particular become the distinctive Christian act of worship - so much so that The Catechism of the Catholic Church refers to the Eucharist as the source and summit of Christian life (CCC 1324)? The answer is that we assemble to offer sacrifice - what Catholics call the Mass. When Jesus took bread into his hands, he said “this is my body, which will be given up for you” (Luke 22:19). What else is a sacrifice other than to give up something for something or someone else. Jesus indeed gave up his body by dying on the cross for our sins. But he also called us to do the same. He said “…whoever does not take his cross and follow me is not worthy of me” (Matt 10:38) and “For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 16:25).

Why is this sacrifice necessary? St. John realized that to understand this, we needed to go back to the beginning. In his Gospel we read: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God” (John 1:1). Who or what is the word? John makes it crystal clear that the Word (i.e. God) is Jesus when he writes: “…and the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14).

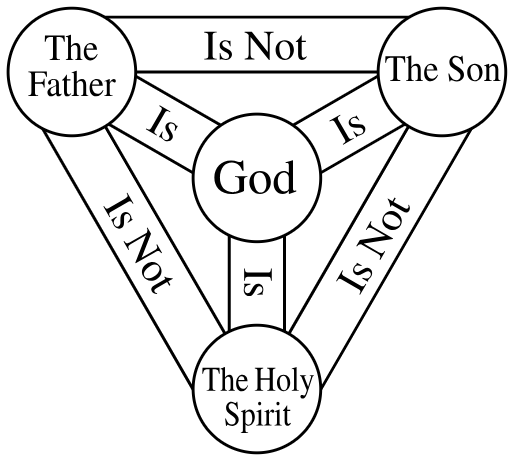

This passage is a foundational text for the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, which holds that God exists as a communion of love between three persons: the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. In this communion, the Father gives his whole self to the Son, and from all eternity the Son gives his whole self to the Father. And from all eternity, this exchange of love between them has been the Holy Spirit. This communion of love is the very picture of fulfillment, ecstatic joy, and unlimited contentment.

As I’ve discussed in a previous post, the fact that this communion is so perfect raises the question of why God would bother creating us at all. Our Christian faith reveals that we literally exist because of his love. You are not an accident. God was not bored; he didn’t create you as a plaything for his amusement. He didn’t need your help with anything; you are not his minion or his slave. He was not lonely, and didn’t need you to tell him how great he is; you are not his emotional support animal.

The truth is that God created you for the same reason a perfectly happy couple decides to have a child in spite of all the expenses and inconveniences they will bring: love is diffusive. When we have, and are totally secure in love, we want to share it with others - we want to start a family, biologically or otherwise. God created you for no other reason than to share in his family. You are his beloved child.

Unfortunately, this perfect harmony was shattered when Adam and Eve turned away from God by disobeying him in the garden of eden. Sin wounded and disfigured our nature, and deprived us of the supernatural life we were created to enjoy. We were in need of a savior because, as St. Anselm taught, ‘the debt was so great that while man alone owed it, only God could pay it.’ This is why “the word became flesh and dwelt among us” - to take on our nature and pay the debt we could not. The debt we owed was a debt of love. Nothing less than a total self gift could pay this debt, and no one else but God could make it.

Through the institution of the Eucharist at the last supper, Jesus teaches and empowers us through grace to love as God loves: total self gift to the Father, even unto death. We are able to give unto death because we have faith in Jesus, and we know that death cannot ultimately take away our life. We know this because in Christ we are joined to God, and God cannot die. Although our human nature will suffer death for a time, in Christ we will one day rise again as he did.

In the Mass, the priest asks the congregation to pray for this offering. He says, “pray brethren that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God the Father Almighty.” This prayer captures what we do in the Mass. We are not mere spectators watching the priest offer the sacrifice. The sacrifice is offered at the priest’s hands, but it is offered by the whole body of Christ. When we go to Mass, we could almost think of blessing ourselves with holy water as our ‘clocking in.’ We have a job to do - a sacrifice to offer. No one else can do it for us.

In your test run today, place yourself at the first Mass - the last supper. Listen to Jesus speak the words, “Do this, in memory of me.’ What are you ‘doing’ when you attend Mass? Do you see it as your sacrifice, or are you merely watching it? If you want to learn more about how to pray the mass rather than merely watch it, check out the video I posted above by Fr. Mike Schmitz. May God bless you as you pray.